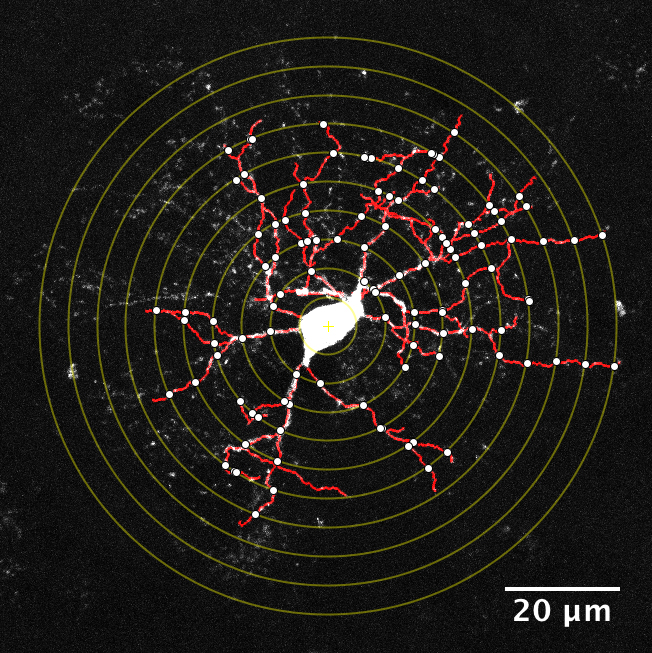

Dopamine neurons of the ventral midbrain contribute to voluntary movement, the processing of natural rewards, and the development of several neurological disorders including Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia and drug addiction. We use a combination of patch clamp electrophysiology and behavioral techniques to investigate hypotheses concerning the role of dopamine neuron excitability in behavior.

The role of dopamine neurotransmission in substance abuse:

Drug overdoses are now the leading cause of accidental death in young Americans. Abuse of synthetic opioids like fentanyl are now rampant, and in many places including Oklahoma abuse of methamphetamine is also an enormous public health issue. While rapid treatments like naloxone can rescue opioid overdose, no therapeutic agent is currently available that targets that addictive process itself for either opioids or stimulants. Repeated exposure to these drugs produces persistent neurophysiological adaptations or “plasticity” at individual synapses in the brain. However, many of these adaptations have yet to be identified, and it is not well understood how plasticity leads to increased drug seeking and intake. We use operant self-administration of methamphetamine in mice to model human drug use, and combine this with electrophysiological studies in dopamine neurons to investigate the synaptic regulation of drug-related behaviors. Determining the neurophysiological adaptations that occur with prolonged drug use is an important first step in identifying intervention strategies to treat human drug abuse.

Role of dopamine in aging and neurodegeneration:

Advanced age is the leading risk factor for the development of neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, suggesting that adaptations during normal aging may contribute to disease development. Unfortunately, very little is known about how neuron physiology changes with age. We use patch clamp electrophysiology of dopamine neurons to identify age-related adaptations in both intrinsic ion conductances and extrinsic synaptic input. We use multiple progressive models of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease to take physiological “snapshots” at different stages of the neurodegenerative process to identify strategies for preserving function at early stages of degeneration.